Yellow fever epidemic, often referred to as “Yellow Jack,” “Yellow Plague,” or “Bronze John,” is an acute viral disease caused by the yellow fever virus (YFV), a member of the Flavivirus genus. It is transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, a vector prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions. The disease manifests with a sudden onset of fever, chills, muscle pain, headache, and notably jaundice, which gives the disease its name.

Virology and Pathogenesis

Yellow fever epidemic virus is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus, approximately 40–50 nm in diameter. The virus enters host cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, leading to fusion of its envelope with the host cell membrane. The viral genome then replicates in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and vesicle packets. The structural proteins of the virus include C (capsid), prM (precursor membrane), and E (envelope). Cleavage of prM in the Golgi apparatus is crucial for producing mature, infectious virions.

The virus predominantly infects dendritic cells, monocytes, and hepatocytes. Infected hepatocytes exhibit cytoplasmic degradation, marked by the presence of eosinophilic masses known as Councilman bodies. Cytokine release leads to a cytokine storm, which, in severe cases, progresses to multiple organ failure.

Clinical Presentation

The disease typically incubates for 3 to 6 days. Most cases result in mild symptoms, including fever, headache, nausea, muscle pain, and vomiting, lasting 3 to 6 days. However, in approximately 15% of patients, a second, more severe phase develops. This “toxic phase” is characterized by recurrent fever, jaundice due to liver damage, abdominal pain, and bleeding, which may manifest as bloody vomit (vómito negro). Kidney failure, seizures, and delirium can also occur.

The fatality rate for those entering the toxic phase ranges from 20% to 50%, with severe cases exceeding a 50% mortality rate. Survivors of the disease typically gain lifelong immunity.

Transmission and Epidemiology

the bite of infected mosquitoes transmit Yellow fever epidemic, primarily Aedes aegypti, although other Aedes species can act as vectors. The virus is maintained in three transmission cycles: urban, sylvatic (forest), and savannah. Urban transmission involves human-mosquito-human cycles, while sylvatic transmission occurs between mosquitoes and non-human primates in forested areas, and the savannah cycle serves as an intermediary between these two.

Despite its presence in Africa and South America, yellow fever epidemic has not yet established itself in Asia, although the Aedes aegypti mosquito is widespread in the region, raising concerns about potential future outbreaks.

Diagnosis and Prevention

Yellow fever is primarily diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and patient travel history. Confirmation of infection can be achieved through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood samples or the isolation of the virus in cell culture. Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), may detect IgM antibodies specific to YFV.

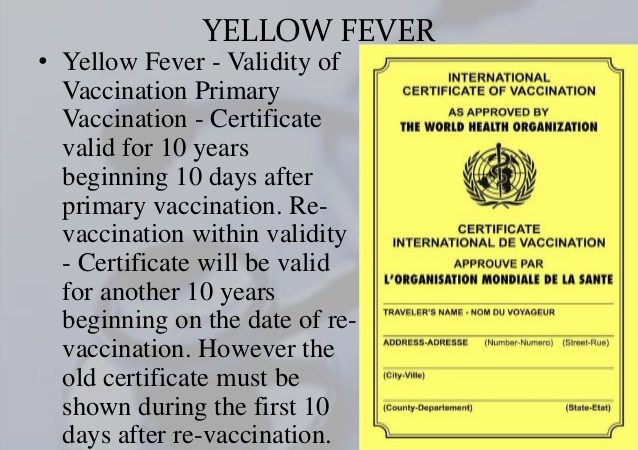

A highly effective live-attenuated vaccine, developed in 1937, provides long-term immunity to yellow fever, and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends vaccination for individuals living in or traveling to endemic areas. Immunization campaigns, such as the Yellow Fever Initiative, have significantly reduced the incidence of yellow fever in Africa. However, in areas of high mosquito density, vaccination alone cannot eliminate the disease.

Historical and Global Impact

Yellow fever originated in Africa and was introduced to the Americas during the transatlantic slave trade. Major outbreaks occurred throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, affecting cities in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. In 1927, YFV became the first human virus to be isolated, laying the foundation for significant advancements in virology.

Despite vaccination efforts, yellow fever remains a public health threat in Africa and South America, with approximately 200,000 cases and 30,000 deaths annually, 90% of which occur in Africa. Factors contributing to the resurgence of yellow fever include urbanization, decreased immunity among populations, and climate changes that expand mosquito habitats.

Conclusion

Yellow fever continues to pose a serious threat in tropical regions due to its high fatality rate and the potential for large outbreaks. Ongoing efforts to control mosquito populations, along with widespread vaccination, are critical in reducing the global burden of this disease.

Yellow fever in Rwanda

The U.S. Embassy in Kigali reminds travelers to Rwanda that proof of yellow fever vaccination is mandatory for entry. Due to a recent outbreak of yellow fever in Angola, Rwandan immigration officials now require air travelers over the age of one who are unvaccinated to receive the vaccine upon arrival at the airport (cost: $40 USD). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends to vaccinate against yellow fever travelers aged 9 months and older . The U.S. Embassy urges American citizens in Rwanda or those planning to visit to get vaccinated for yellow fever if they haven’t already.

We advise all citizens to remain vigilant in taking anti-mosquito precautions, which include: avoiding areas with standing water where mosquitoes breed, staying indoors during early morning and evening twilight hours, using mosquito repellents, and sleeping under mosquito nets.

Additionally, American citizens should be alert to the signs and symptoms of yellow fever, which are similar to those of malaria. Symptoms include sudden fever, fatigue, weakness, chills, severe headache, joint pain, body aches, nausea, and vomiting. If you experience these symptoms, promptly seek medical attention.

For further information about yellow fever, please visit the CDC’s FAQs about Yellow Fever.